Home | Pioneers | Contact Us | Copyright/Disclaimer

David Parry-Okeden

c1839 Monaro

|

|

|

|

|

These images and the following document were supplied by Ian Parry-Okeden

History

Excerpt from

A SON OF AUSTRALIA

MEMORIES OF W. E. PARRY-OKEDEN I. S . O . 1840—1926

Related by HARRY C. PERRY

BRISBANE: WATSON, FERGUSON & CO LTD, 1928

CHAPTER II

Australia in 1830—On the Barrier Reef—Encounter with Natives—Land deal with Maoris—Queen Victoria's Coronation—A Story of Mutiny— Under the Southern Cross Once More—A Wild and Beautiful Land— On the Snowy River—Birthplace of W. E. Parry-Okeden—Vindictive Savages and Desperate Outlaws.

LIEUTENANT DAVID PARRY-OKEDEN was 19 years of age when certain tyrannical incidents of which he was the subject decided him to leave the Naval Service, and he expressed a desire to visit Australia. His father suggested a commission for him in the Canadian Mounted Rifles, but it transpired that the youth was just one year too old to join this force and eventually it was agreed that he should have his way. With £l000 in his pocket to start him in life David Parry-Okeden embarked at Liverpool for Sydney, the passage costing him £75. Arriving at his destination after a tedious voyage he spent a month looking around the young colony, and in the absence of any better prospect he accepted the command of a schooner called the "Clementine," about 130 tons. He made two trips in her from Newcastle to Hobart carrying coal and returning with potatoes and apples. The owner, a Frenchman named Dudoit, then fitted her out for a cruise along the Great Barrier Reef in search of beche-de-mer, and young Parry-Okeden put all his available capital into the venture with Dudoit, who sailed with him. They cruised about from reef to reef with tolerable results and many adventures. On one occasion they ran into Princess Charlotte Bay for water and were threatened by a large party of natives upon whom they had to fire in order to drive them off. After a cruise of about eight months they ran to Timor where they sold their cargo and loaded up with ponies and sandalwood which they disposed of at Batavia. Here the craft was purchased by Messrs. Douglas MacKenzie and Co., who fitted her up to recover portion of the cargo of a large ship that had been stranded on the Louisa Bank on a voyage to China. Mr. Okeden was offered the command, with a half share of whatever was recovered. As it was the change of the monsoon he declined. It was a fortunate decision as it turned out for the schooner, having set forth on her mission, was not again heard of. After some time in Batavia Mr. Okeden embarked in a ship called the Mary Ann, for the Cape of Good Hope, carrying a cargo of rice and sugar. Thence he obtained a passage in a ship called the Red Rover bound for Sydney. She was under the command of her owner, Captain Christie, whose young wife accompanied him on the trip. Everything went well until the ship was within sight of St. Paul and Amsterdam when a gale sprang up. The ship drove merrily before the wind until the watch was being changed at midnight when the man at the wheel allowed the ship to broach to and a heavy sea broke over her. Mr. Okeden sprang from his cot on the main deck, rushed to the wheel, and was just commencing to pay the ship off again when Captain Christie came on deck in oilskins and sea boots. Another sea broke over the ship at that moment, and as Mr. Okeden shouted a warning the captain lost his footing and was washed overboard. The ship was promptly hove to, some hen coops thrown overboard, and a boat lowered, but the unfortunate commander was never seen again, having evidently been hampered by his heavy clothing in any attempt he could have made to battle against the raging elements. When the news was broken to Mrs. Christie there was a pathetic scene. In the ordinary course the first mate of the vessel should have succeeded to the command, but Mrs. Christie, to whom the ship and most of the cargo was left by her husband's will, had taken a dislike to this officer, and at her request Mr. Parry-Okeden navigated the ship first to Hobart and thence to Sydney.

On arrival at his destination Mr. Okeden found letters awaiting him informing him of the death of his father who had left him a sum of £6000. He thereupon decided once more to leave the sea, and he rented a farm at Minchinberry, between Parramatta and Penrith, where several convicts were assigned to him as labourers and servants. The venture did not turn out a success financially. He then joined in a syndicate which purchased a large tract of land in New Zealand from the native chiefs, a form of speculation which attracted a good deal of attention at that time. The British Government declined to ratify the deal in the form in which it was made but allowed each member of the syndicate to retain 20,000 acres for which they had to pay at the rate of 1/6 per acre. One member of the syndicate was deputed to look after the concession on behalf of the whole party and was given power of attorney to act for them, the outcome being that he eventually became the possessor of the whole of the land and a very wealthy man in consequence.

David Parry-Okeden now decided to revisit England and he arrived at Dover, after a four months’ trip in the brig Craigevar, on the day that Queen Victoria was crowned (28th June, 1838). On reaching home he learned of the death of his sister. He was one of the beneficiaries under her will and also obtained a further sum from his father's estate, making in all £5000. Shortly after arriving the real purpose of his visit became manifest when he married Rosalie Caroline Dutton, daughter of an ancient Chester family, and a descendant of Baron Sherbourne, through whom the family goes back to Odard, who came in with the Conqueror. A cornelian seal bearing the family crest of the Duttons, was left to William Edward Parry-Okeden by his uncle, Hannibal Dutton. David Parry-Okeden now purchased a couple of hunters and with his young wife, who was a splendid horsewoman, spent some months very happily as the guests of his uncle, George Harris, Esq., hunting with Lord Portman's hounds.

The holiday ended David Okeden again turned his mind to the land of the Southern Cross, and with his wife set sail for Sydney in a ship called the Eden, a fine craft of 1500 tons, fitted with large cabins and every comfort then obtainable for sea travellers. There were 19 passengers on board altogether, including Mr. and Mrs. Okeden, Mrs. Okeden's brother, Hannibal Dutton, and Henry William Haygarth, a cousin of Mr. Okeden. Before the vessel had proceeded far on her voyage the captain gave way to drink. This led to difficulty with the crew who were soon in a state of mutiny. Several exciting incidents having made it plain that the position was serious, Mr. Parry-Okeden insisted that all the passengers and such of the crew as could be absolutely depended upon should be armed. They were mustered under arms upon the alter deck and the malcontents having been summoned they were addressed by the captain, who said: “This ship is in a state of mutiny which must be suppressed. I delegate my authority to Mr. Okeden; an old man’o’warsman; to act in any way he deems best bring this state of mutiny to an end. Mr. Okeden thereupon ordered the boatswain to be placed in irons, with a threat that he would be run through if he offered any resistance. The mutineers were next ordered aloft to take a reef in the foretopsail. They recognised that they had to deal with a man who his business, and in whose ability as a navigator they could have full confidence. They obeyed orders without further trouble and the mutiny was over. It was an anxious and exciting time for everyone on board, and particularly for Mrs. Parry-Okeden, who often told the story in after years. The boatswain was several times threatened by the captain when the latter was in his "cups" and on the man promising to behave Mr. Okeden accordingly released him.

As the ship was getting short of provisions the passengers expressed a desire that the captain should put into Capetown. The captain objected, but upon Mr. Okeden consenting to act as pilot he ultimately agreed and a pleasant 10 days was spent in port. A few days after leaving they sighted a ship which appeared to be on fire and as the wind was fair they bore down upon her. It turned out to be a whaler trying out the oil from a dead whale which was moored beside the ship. Mr. Okeden went on board the whaler and spent a pleasant half hour with her captain watching the process of trying out the oil and being no less interested in the flocks of albatross and numbers of sharks, each fighting for their share of the whale's carcass. The captain of the Eden now shaped his course to pass around the end of Van Dieman's Land instead of going through Bass Straits. Mr. Parry-Okeden remonstrated and the captain agreed that he should pilot the ship through the Straits. This was done and eventually Sydney was reached in safety after a voyage sufficiently exciting to satisfy the most adventurous.

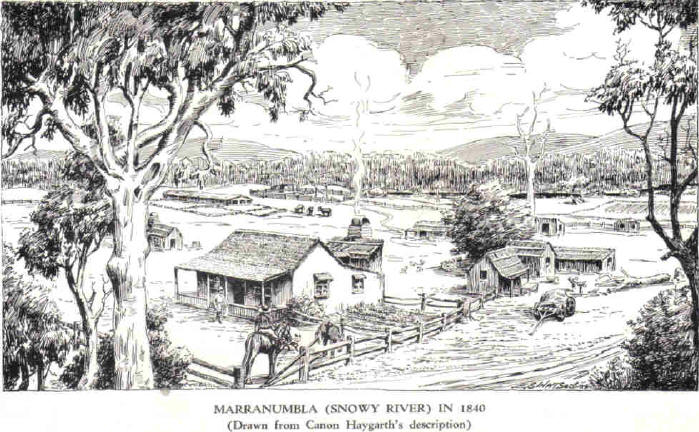

Having determined to make his home in Australia, Mr. Parry-Okeden at once cast about him to find a property suitable to his means. He visited the districts of Bathurst and Goulburn, and ultimately penetrated to what was then called the Maneroo district, which was practically as far as settlement had gone. Passing over the Kamberra country, upon which the Federal Capital of the Australian Commonwealth was to subsequently arise, He reached the banks of the Snowy River, where, for the sum of £4700, he purchased a property called "Marranumbla," from the firm of A. B. Smith and Co., of Sydney The station situated in the heart of the wild and beautiful country of which Henry Kingsley was to write many years later in his story of "Geoffrey Hamlyn." It was of mountains and torrents, of rich scrubs and delightful scenery, with the majestic peaks of Mt. Kosciusko towering over all. It was a nine days’ ride on horseback from Sydney to Marranumbla, and it was by this method of travel that Mr. Parry-Okeden and his gallant young bride reached their home. Some idea of the country and its conditions be gathered from a book written by Henry William Haygarth, Mr. Okeden's cousin, some years afterwards. This gentleman, who accompanied the young settlers and spent some time on their property, was in later years ordained a priest of the Church of England and became Canon Haygarth of Wimbledon, England. His book was entitled "Recollections Life in Australia," and it was published in 1848 by John Murray, Albermarle St., London. It was evidently intended for the hundreds of young men of good family who were then being drawn to Australia by dreams of fortune easily won, and it must have been of great assistance in that direction. He points out that the journey from Sydney to the Snowy River had to be made on horseback He writes: "The only public conveyances were the mail coaches which for certain distances from the capital were tolerable enough, but at each change they gradually dwindled from good to indifferent, and from indifferent to grotesque until at last the traveller finds himself in a vehicle to which the name of coach can be applied only by courtesy or by metaphor. But on horseback he is thoroughly independent; the valise neatly strapped in front of his saddle contains his whole wardrobe, and being master of his own time he can dispose of it to the best advantage When the weather is hot he can indulge in a few hours rest at noon, while his horse crops the herbage around, and to make up for this delay he will push on during the cool of the evening. If he is not wholly destitute of the organ of locality he can make many a short cut that will sensibly diminish the length of his journey."

"There is nothing more pleasing,” he continues, “during a journey up country, after a long ride through the forest, than to emerge towards evening upon some clear and verdant space, surrounded by woods, not terminating abruptly, but shelving down and opening gradually as if placed there by the hand of Nature to form a picturesque fringe to the plain. There is now a brief but delightful change of sight and sound; the chirp of the locust ceases and the murmur of lowing herds and bleating flocks soothes the ear; the eye dwells refreshed upon a variety of water and pasture, whilst marking the distant white smoke which curls against the dark background of wooded hills and points out the habitation of man The coach-whip, with its peculiar jerking cry, excites the curiosity of the stranger, and the bell bird—never found but in the vicinity of water—adds its musical note." Mr. Haygarth goes on to describe the approach to Marranumbla thus: "The sun was sinking for the ninth time since our departure from the shores of Port Jackson as our horses stopped to drink at the ford of a pebbly margined river that ran in front of our station. The stream thus briefly indicated was the Snowy River and the ford became Buckley's Crossing. Around and about it there was destined to grow up the important town of Dalgety, situated just outside the Federal territory of Canberra and itself one of the centers which was considered by a Royal Commission, appointed after the establishment of the Commonwealth, to select the most suitable site for the Capital City of Australia. Of Marranumbla homestead, Haygarth wrote:

“In front was the owner's residence, a better sort of wooden cottage, chiefly distinguished on the outside by a verandah. Behind and on either side were huts for the working men. The wool shed, a long rambling building, surrounded by several low sheep yards, stood out by itself; while on a distant flat appeared a large space fenced around for a wheat paddock. In another direction a most formidable looking enclosure covering about half an acre of ground formed the stockyard for the cattle. The whole was backed by low hills, thinly wooded and agreeably receding in the distance, and at the foot of these appears a chain of clear ponds or waterholes."

The foregoing depicts pleasantly enough the home and property to which David Parry-Okeden took his young wife and where on the 13th day of May in the year 1840 their only child William Edward Parry-Okeden was born. But it is difficult for the modern reader to visualise all the primitive conditions under which the young settlers were called upon to live. Railways and motor cars, of course, there were none. Primitive tracks over virgin soil were all that existed in the shape or roads, and a light gig, in which Mr. Okeden usually drove two horses tandem, was the only kind of vehicle that could be depended upon to get safely and quickly over the country. Electric light and power, which is common now on so many outback stations, was then unknown and even matches had not come into use, fire being obtained by the primitive flint, steel, and tinder box or (when the conditions favoured) by means of a sun glass. The mysterious depth of the bush which surrounded the homes of the pioneers was known to be the hiding place of bands of naked savages, in many cases rendered vindictive as a result of having been driven from their hunting grounds and of having been otherwise ill-treated by the white invaders of their domain. And much worse than the blacks were the parties of bushrangers; criminals who had escaped from the convict settlements; men who had been brutalised and degraded to the last degree, and who were rendered desperate by the knowledge that nothing, but death or worse awaited them if they were recaptured.

Even the means of defence against attack by black or white marauders was of the most primitive kind for practically the only firearms were of the old flint lock type. Mr. Parry-Okeden took the first gun fired by means of a percussion cap into the Maneroo (afterwards called the Monaro) district. This gun, a rifle which had belonged to his brother in India, and a couple of double-barrelled muzzle loading shot guns, quite a considerable armory, and became the object of envy by at least one party of bushrangers as will be related later At this time, too, practically the only labour available, either for domestic or field consisted of convicts, men and women who were out on ticket of leave and assigned to those who had work for them to do. Sydney was the only township of consequence, and that was nine days’ journey from the homestead. Just what that journey meant, particularly to a woman, may be gathered from an incident which occurred on one occasion. Mr. Okeden had driven his wife to Sydney and they were returning to Marranumbla in the gig when they put up for the night at a place called Myrtle Creek. In the morning they were preparing to start, but the landlord of the hotel, with a very serious face, advised them not to go on as bushrangers were out in the Bargo Scrub some miles from the settlement of Berrima, where a considerable town afterwards sprung up.

It need not be remarked perhaps that neither Mr. Parry-Okeden or his wife were of the nervous sort and they were well aware of the weakness which the bush publican of that day had for delaying the progress of travellers, who might be likely to spend a little for good accommodation. Mr. H. W. Haygarth thus refers to this penchant: "In less steady climates country innkeepers are said to avail themselves of their weather wisdom to detain a hesitating guest by prognostications of bad weather. The dry atmosphere and cloudless skies of Australia drive the cunning host to a different resource, but one still more efficacious with new comers to the colony, and that is the prevalence of bushrangers, who, somehow or other always manage to infest the roads by which the traveller is destined to travel. These stories are occasionally too true, but so many are fabrications that perhaps the best way is to turn a deaf ear to them altogether. However, the stranger who listens to them will find them full of incident and very alarming. He will be informed how Mr. Longbow, the member of Council, was stopped only yesterday and robbed of his horse, valise, and all of the etcetera's by the "croppies," —Black Joe, or Irish Jim—one of whom afterwards relented and gave him back his inexpressibles. Or there will be an account of the disasters which befell Mr. Woolpack, the rich Bathurst settler, who, being suspected of tyrannising over his men, was tied up to a gum tree and only saved from a severe infliction of the stirrup leather by a false alarm of "Police," upon which the bushrangers had decamped leaving him in a state of bondage where, at night fall, he would have been surely eaten alive by native dogs had he not been discovered and released by some gentle shepherd."

The travellers on this occasion were determined that they would not be upset by any publicans bogey, and so they decided to continue on their journey By way of precaution, however, Mr. Parry-Okeden loaded a couple of double-barrelled duelling pistols, which he always carried, and in order that they might be quite handy he placed them in their case, open on the lap of his wife as she took her seat beside him in the gig. He was determined to keep a sharp look out for any robbers who might possibly beset him and in looking him with this object he failed to notice a stump against which one wheel of the vehicle struck, throwing Mrs. Parry-Okeden to the ground. When he went to her assistance she greeted him with a laugh for she had fallen quite unhurt in a sitting position, and there she was with the loaded pistols still in her lap. Continuing their journey they soon came upon a small party of travellers who were camped by the roadside with their drays They had just been stuck up and robbed by the bushrangers, and one of their number who had unfortunately recognised the leader gang and had been so ill-advised as to make the fact known, was promptly shot dead. His body was lying in the middle of the road whilst his wife and two children sat in their dray near by, weeping and lamenting at the grim tragedy that had deprived them of their bread winner. Mr. Parry-Okeden pushed on as fast as his tandem team could go to the settlement at Berrima where he informed the police of what had happened. A posse of troopers at once set out for the scene and coming up with the outlaws a sharp engagement took place in which the police succeeded in shooting two of them.

At this time it was customary for the settlers to make all their payments to their employees in gold. There had been a number of cases in which unscrupulous men had taken advantage of their uneducated servants and had paid them with cheques or orders, which turned out to be worthless. This led to a general insistence on payment in gold. At the time of the incident just related Mr. Okeden was returning to Marranumbla with a considerable sum in sovereigns, which he carried, according to the custom of travellers at that time, in a belt about his waist and concealed beneath his clothes. Had he met the outlaws there is little doubt that they would have endeavoured to search him and his wife, and with a man of his fighting spirit a tragedy would have been inevitable. It was suspected at the time that the leader of the gang was a man named William John Westwood, who was known as "Jacky Jacky." During his career of crime he escaped first from Cockatoo Island (Sydney), then from Port Arthur (Tasmania), and he was ultimately executed at Norfolk Island in 1846.

The vicinity of Berrima was much favoured by the bushrangers at this period. Some time after the adventure just related Mr. Parry-Okeden was returning from Sydney to Marranumbla when he had a personal encounter with them. On this occasion he was travelling alone and on horseback. He was carrying a large sum of money in gold in the belt about his waist. Night overtook him on the road, but not wishing to camp out in such a dangerous locality, and as there was a bright and early moon, he decided to push on to the settlement. He was about three miles from Berrima when four men, all of them on foot, sprung at him from the shadow of the trees and as they attempted in seize his horses bridle they called upon him to "bail up." Discharging his pistol at the nearest man Mr. Okcden simultaneously put spurs to his horse and dashed through the outlaws. Several shots were fired after him, but happily without result, and he continued without drawing rein until he reached the hotel at Berrima. Word had gone round that there were bushrangers about and hearing the approach of a galloping horse the occupants of the house dashed out armed and ready to repel attack. Some of the more nervous were inclined to suspect the worthy settler of being himself a bushranger until he was able to make himself known.

CHAPTER III.

Discovery of Gippsland—Angus McMillan's Part—Armulet of Human Hands—Port Albert Settlement—David Parry-Okeden's Explorations—Rosedale Station Formed—On the Glengarry River— Bushrangers Visit Marranumbla.

THE changes that have taken place in one man's life may be realised if we take a bird's eye view of Australia, as it was in the year that W. E. Parry-Okeden as born. It was in 1840 that effect was given to the annexation of New Zealand by Great Britain. Van Dieman's Land had enjoyed existence as a Colony apart from New South Wales for 15 years only, and all the horrors of which Marcus Clarke was to write later were still being perpetrated. Moreton Bay was the settlement furthest north, and the penal period had not yet given place to free settlement. It was only five years before that John Batman had crossed from Tasmania, and, passing up the river Yarra Yarra, had made his famous trade with the natives for an area of about 600,000 acres of land, including the site of Melbourne, in return for a quantity of blankets, knives, mirrors, and beads, a deal which, like that made about the same time by David Parry-Okeden and his friends in New Zealand, was disallowed by the authorities. It was not until W. E. Parry-Okeden was 11 years of age that the Colony of Victoria came into existence and he was in his 20th year when Queensland in its turn secured separation from New South Wales. The rich and beautiful territory of Gippsland, destined to be called the "Garden of Victoria", was then a terra incognita, and as this was to become the scene of young Okeden's boyhood it will be interesting to place on record here the manner of its discovery. Mr. P. J. Wallace, writing of "The Genesis of Gippsland," points out that in 1839, before

The gold era, Gippsland was an unknown wilderness, half-savage sailors, who frequented the islands off Bass Straits, occasionally made raids on the coast and carried off native women, but the country itself repelled exploration. From Melbourne the progress of civilisation had been arrested by dense timber, low scrubby ranges, and morasses surrounded by thick ti-tree. On the north and north-east the barrier of the Australian Alps soared skyward as far as the head of the Murray River. On the New South Wales side of the present boundary settlement had extended from Sydney to Twofold Bay and the Monaro district then called Maneroo. Reports had been received from the blacks of fine open and grassy country over the Alps to the south west. Vain efforts were made to reach it, and a man named McKellar had penetrated the barrier as far as the Omeo High Plains (then called Omio). There he formed a cattle station, but the climate was very severe and he got no further. The man who succeeded, after several attempts, was Angus McMillan, then 30 years of age. Born on the Isle of Skye he had been in the Colony for nine years. He was employed as overseer at Carrawong Station in the Maneroo district by Mr. Lachlan McAlister, of whose family there is much interesting information in a book called "Australian Bush Tales," written by George Dunderdale. On the 29th May, 1839, he started with Jimmy Gibber, a chief of the Maneroo tribe, to reach the country spoken of by the blacks. They travelled south-west for five days and from the top of a high mountain, which he named Mt. McLeod, he had a good view of the plains, lakes, and sea. The country was very rough and his companion, becoming alarmed on account of the wildness of the natives around, refused to go further. McMillan, however, decided to go on. That night he woke up suddenly to find the chief standing over him with raised waddy. He grabbed his pistol, and the native, having been cowed into submission, explained his action by saying that he had been dreaming that another native was carrying off his lubra. After this narrow escape McMillan decided to turn back.

For his next trip a bullock dray and provisions were obtained from Sydney, but it was only after innumerable hardships that the dray was got over the mountains and once it took three days to climb a pinch of nine miles. A point about 50 miles south of Omeo was at last reached. This the natives called Numbla Mungee and here a station was formed from which the next station to the new country could be started. On the 29th December, 1839, McMillan, McAlister, Cameron, and a stockman named Bath, started out from Numbla Mungee with several weeks' provisions, the object being to reach Corner Inlet, where it was hoped to find a suitable point from which to ship cattle to Tasmania and Sydney. They camped the first night on the banks of a river (the Tambo) One day McMillan was riding ahead when he came upon number of blacks, who were astonished at the first horse and rider they had ever seen. The explorer dismounted and made friendly signs, but they fled in terror and all day the terrified wailings of the gins and piccanninies were heard. Years later some of these blacks told McMillan that they had thought he and horses were the one creature. The travellers pushed on, cut a track through the scrub to the river and crossed over by logs, carrying their saddles and provisions, whilst they swam their horses over with the aid of guide ropes The ranges on both sides were so steep that the pack horse rolled down until stopped by a tree and it was so badly hurt that they decided to return, the second attempt to conquer the fastnesses thus failing.

For the next attempt the services of two Omio blacks were obtained A chief of this tribe, Cabon Johnny, was one and the other was called Friday. They started on 11th of January 1840, travelled their old tracks to the Tambo river, and then followed it to the point where it enters a lake which McMillan named Victoria. This was alive with duck, swans, and pelicans. This part of the lake was afterwards called Lake King. The country was good. Kangaroos and emu plentiful, and grass as high as the saddle girths. They travelled west along the lake, and on January 17th, came to a river which they called the Nicholson after a Sydney doctor. This stream was too deep to cross so they followed it up to the ranges where they scrambled through a rocky ford. The weather was fearfully hot and the meat went bad, but one of the party shot a duck and this saved the situation On the 18th another river (which McMillan called the Mitchell) barred their way. They followed it up, having some difficulties in the morass. From the top of an adjacent hill, McMillan obtained a splendid view of the surrounding country, which he called "Caledonia Australia." On the 19th January, the Mitchell was crossed and travelling south-west the party camped at a place which they named Providence Ponds. On the 21st, they sighted a large lake which at first they thought to be a continuation of Lake Victoria, but the water was salt instead of fresh, and they called it Lake Wellington. Numbers of blacks were seen, but they ran away. On the 22nd, they crossed the Avon about two miles from the hills. The country now consisted of fine, open plains with occasional belts of timber They had a fine view of the mountains to the north and McMillan named it Mt. Wellington. They travelled south-west all day and struck another river which they named the McAlister. Native signs were numerous. They tried to cross the stream on the 23rd, but failed and followed it down without observing its junction with the Thompson. They then reached the morass below the point on which the town of Sale was afterwards to arise, where the Thompson and the Glengarry join. Hundreds of blacks were seen, but they would not parley with McMillan's blacks and ran away. One old fellow who was too lame to run was questioned and signs were made to him that the travellers wished to reach the sea, but without result. He was given an old pair of trousers and a knife. His only ornaments were several human hands, doubtless removed after death, bound round at the wrist and with the little finger turned into the palm. These relics had been dried in the sun and were worn suspended about the neck. An attempt was next made to strip bark from a tree for the purpose of making a canoe, but the bark split. A consultation followed and as the provisions were now low McMillan's companions overcame his desire to go on and it was decided to return with a view to bringing back stock and occupying the good country passed through near the Avon. Seven days were occupied in the return from this, the third trip, by McMillan. On the 31st January, McMillan reported his experiences to his employer at Maneroo, and subsequent events indicated that information of what had been found in the new territory was given to some Maneroo settlers, including Mr. David Parry-Okeden, probably by McAlister himself, as he was not prepared to take advantage of the discoveries. He was firm in the conviction that a port was necessary from which stock could be shipped before the new territory would be of any great value.

At this point, as Mr. Wallace points out, another steps in with a claim to be the discoverer of Gippsland. Count Streslecki, a Polish scientist, who had discovered Mt. Kosciusko, fitted out a party at Government expense, with survey instruments and pack horses. They arrived at Numbla Mungee, whilst McMillan was absent at Maneroo, and after replenishing their provisions, and obtaining a camp kettle from McMillan’s stores they started out on March 27th, two months after McMillan’s return to Maneroo. Matthew McAlister, who had been with McMillan, accompanied the Count for one day explaining the rivers to be crossed and pointing out the tracks of McMillan’s party which Tarra, a black from Sydney, said he could easily follow. Streslecki and his party reached the Latrobe, but a few days later they struck trouble, because of the impenetrable scrubs. Being short of provisions they had to abandon their baggage, including their instruments, and they attempted to force their way to Westernport on foot. For 21 days they struggled over ranges, through dense scrub and morasses, sometimes up to their waists in water and sometimes hacking their way with tomahawks. For over two weeks they lived on the flesh of native bears which at times they had to eat raw. Broken down and enfeebled by starvation the ragged party managed to reach Westernport on May 12th, 1840, the day before the birth of William Edward Parry-Okeden at Marranumbla and when David Parry-Okeden was himself exploring the country about the Glengarry River.

A fourth attempt by McMillan to clear a road across the mountains to the new country was interrupted by orders from McAlsiter, but on the 14th July, he started a fifth time, accompanied by Lieutenant Ross, McAlister, Bath, McLaren, and a native. In 12 days he reached the Glengarry, but the river was so high with the winter rains that they could not cross and the party returned to Numbla Mungee. In October, 1840, he started again with a draft of cattle with which he founded a station on the Avon River, afterwards called Bushy Park. In a 6th attempt to reach Corner Inlet he got to within 16 miles, but the scrub stopped him. He named a mountain Toms Cap, because it resembled Tom McAlister’s head dress. Soon after this McMillan endeavoured to establish his rights to the land he had selected but the Commissioner for Crown Lands advised him that as he had gone so far afield he must protect himself. On returning McMillan found that the men he had left at Bushy Park had been driven by wild blacks, his cattle speared or scattered, and the station hands had been chased for 25 miles, eventually reaching Tambo station. McMillan, Dr. Arbuckle, Bath, McLaren, and three others then set out to teach the natives a salutory lesson and this was done, some of the scattered cattle being recovered. When things had again become quiet McMillan, McAlister, four stockmen, and a black started for the seventh time to try and reach the sea from the new country. They left on 8th February, 1841, McMillan having definite instructions from his employer to abandon the new country unless an outlet by sea could be discovered. They crossed the Glengarry and camped on Merriman's Creek. It took a day to cut a track to the top of Tom's Cap, where their toil was rewarded by a splendid view of the long looked-for promontory and inlets. They camped at Bruthen Creek on 12th February. On the next day they reached the sea and found the river Tara. On the 14th they found a suitable shipping point with 7ft. of water at low tide which came to be known as Port Albert. McMillan returned to Avon station by 20th February, and then started out to get his dray through to the new port. About six weeks before this a small steamer named the Clonmell had left Sydney for Melbourne with passengers and cargo, and was wrecked near the entrance to the Port Albert Channel. Vessels were sent from Melbourne and they rescued the crew and passengers who reported having seen good country in the vicinity of the disaster. A company of squatters and merchants, called the Port Albert Co., was at once formed to test it. They reached Port Albert with horses, cattle, and goods, shortly after McMillan’s first visit. On his return, after three weeks' battling to get his dray through, one can judge of his astonishment at finding a settlement where so short a time before there had been wilderness only. David Parry-Okeden was naturally interested in the work that was being carried out by his neighbour Lachlan McAlister of Carrawong and his interest was heightened by the fact that matters were not progressing well with him at Marranumbla. A very hard winter had been experienced and catarrh broke out amongst his sheep, causing heavy losses. On top of this the firm that had been acting as his agents in Sydney, failed for a large sum of money, causing him some embarrassment. The prospect of taking up better country in the newly discovered territory of Gippsland consequently appealed to him and he set out on a journey of exploration at the beginning of April. He spent four months on this expedition and was much impressed with what he saw. It was during his absence that his son was ushered into the world, his heroic wife having been assisted in her time of travail by an aboriginal woman who had become attached to the household and devoted to its mistress. During his explorations David Parry-Okeden was impressed with some country on the banks of the stream which McMillan had named the Glengarry, but which was subsequently renamed the Latrobe River. He decided to take up this country and leaving his overseer in charge with instructions to make a start with the necessary huts, he made his way back to Marranumbla to bring over the stock required for the new station. It was a long and tedious journey, but at last it was accomplished. On reaching the property, which he had decided to stock, however, the young settler found that it was claimed by Mr. McAlister. He had to shift further up the Glengarry River in consequence, and there he took up what he described as "a very nice piece of country upon which we erected our homestead." He called the station Rosedale, after his wife.

There is evidence that David Parry-Okeden for a time contemplated carrying on both his Monaro and Gippsland properties for he left his overseer, Henry Kersley, in charge again at Rosedale, whilst he returned to Marranumbla and he continued operations there for some time. It was during this period that the Snowy River homestead was visited by a noted bushranger named Buchan Charlie and a companion. This man had been transported from England, but soon after his arrival he obtained his ticket of leave and was hired out to service. He ran away from his employer, however, and took to the bush, the reason he gave being that his employer had paid him for his work with a valueless cheque which he was arrested for trying to cash. This injustice, he declared, so preyed upon his mind as to make him desperate. Buchan Charlie knew something of Marranumbla, having been employed there for a time, and he knew all about the very up to date firearms which Mr. Parry-Okeden possessed. These he determined to possess, and he made no secret of his determination. Mr. Parry-Okeden and his young wife spent many anxious days awaiting the threatened call, but the bushranger did not come and pressing work requiring attention at what was called the Heifer Station, some distance away from the homestead, the young settler went off for a few hours. Evidently his movements had been watched, for soon after his departure Mrs. Parry-Okeden was alarmed by the appearance of two armed men riding up to the house. They began operations by ordering the hands into the kitchen where one of the outlaws kept guard over them. The leader meanwhile swaggered into the dining room where the terrified mistress sat with her infant. "You know me Mrs. Okeden," he said jauntily. "Yes, Charlie, what do you want? she replied. "Well!" said Buchan Charlie, "I have come for those wonderful guns. And I want any money you have got." After a moments pause, he added: "I want a change of clothes, a saddle, and a bridle." Putting on a brave face Mrs. Okeden replied: "You know my husband is away. My brother (Mr. Button), and Mr. Haygarth are with him and they have each taken one of the guns. You know, too, that we never keep money in the house." Buchan Charlie then demanded any jewellery available, but again he was put off with the declaration that there was nothing of value, though at that moment a fine gold chain about her neck was concealed by her bodice. Whilst this conversation was in progress Buchan Charlie crossed to the mantel upon which lay a pair of silver mounted pistols which he examined with much interest.

However, they apparently did not impress him as being suited to the grim business upon which he was engaged and when the infant, Willie, reached out from his mother's arms, attracted by the shining weapons, the bushranger placed one in his hands with the remark: "All right little man, I won't take your gun."

"Come on Charlie, bring the Missus with you," cried the second outlaw at this stage, putting his head through the door. Mrs. Parry-Okeden turned sick with horror at the suggestion and clasping her child she looked about for a way of escape. Buchan Charlie, however, turned on his companion in a passion and drove him from the door. "I won't let anyone hurt you," he said. "I've never hurt a woman and I never will. If he attempts to touch you I'll shoot him."

With her fears somewhat allayed, Mrs. Okeden then directed the outlaw to a room off the dining-room wherein there was a wardrobe containing her husband's wearing apparel. "Take what you want and get away for the sake of Heaven," she cried. Whilst the bushranger was turning out the wardrobe and making a selection the anxious young woman was walking up and down the dining-room with her child and in doing so, she passed the partially open door of another room in which stood the precious firearms which the outlaw sought. Stepping lightly into the room she seized first one gun and then the other, dropping them noiselessly through the window into a patch of cultivation outside, where they fell without attracting attention, and then she resumed her pacing of the dining-room. Having selected the clothing he needed Charlie next examined the room from which the guns had been removed only two minutes before, but it did not occur to him to look through the window. Finding that a portmanteau of Mr. Haygarth's was locked he cut it open and then appropriated a new saddle and bridle of Mr. Dutton's. After helping themselves to some food the bushrangers took themselves off. One of the gang was subsequently shot in a raid upon the home of a settler named McIntyre, and Buchan Charlie was eventually captured, a sentence of transportation to Tasmania following.

CHAPTER IV.

Marranumbla Sold—A Trying Journey—All Day through Snow— The New Homestead—Black Marauders Punished—A Woman's Courage—Solace of Music—Turnbull's Stores at Port Albert— Primitive Methods of Shipping Stock—A Visit to Hobart Town—W. E. Parry-Okeden Baptised.

THE difficulties which had beset David Parry-Okeden, and to which reference was made in a previous chapter, were accentuated when the Bank of Australia, in which he had some funds, stopped payment. This finally decided him to sell Marranumbla and to make his home at Rosedale. With his wife and infant son he rode forth again, and in some notes of the journey which followed he wrote: "Our route was precipitous and the cold going over the mountains at Omeo was very severe. We travelled through snow for the whole of the day and camped at Bruthen Creek, one of McMillan’s camps. I carried Willie all through the journey from Maneroo on a pillow, which was lashed on the front of my saddle. Our next camping place was on the south side of the Mitchell River. This was running very high, but we managed to struggle through. My stockman got into a deep hole and was washed off his horse but I grabbed him as he was floating past, and so we eventually landed all safe. The next day we reached our new station and my wife liked it very much. The grass and herbage left nothing to be desired."

|