Home | Pioneers | Contact Us | Copyright/Disclaimer

John Thomas

Lobbs Hole Late 1840’s

Photo supplied by Marg Denley [mldargyll-at-bigpond.com] 24.01.11

Material submitted by Trish Cassidy <cassidy-at-canberra-teknet-net-au>

TEXT OF LETTER WRITTEN BY CJM THOMAS TO THE SNOWY MOUNTAINS HYDRO-ELECTRIC AUTHORITY DATED 18 JUNE 1962

Dear Sir

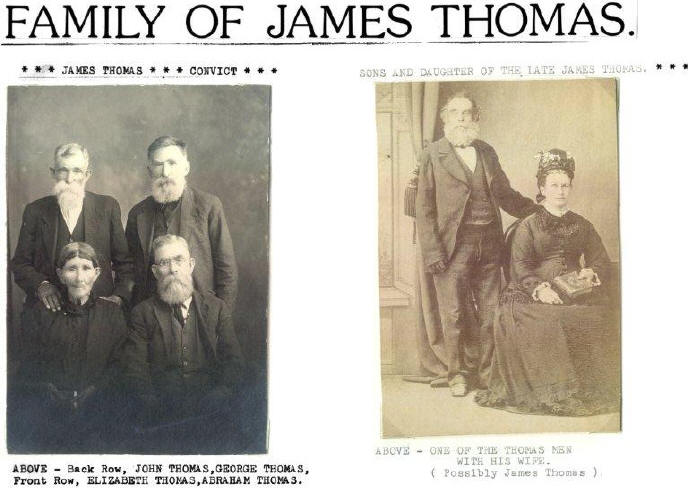

In reply to your letter dated 23 May 1962, I wish to advise that it was John Thomas, my father, who was the first man to select a secured tenure of land in Lobs Hole. 2,840 acres was the limit the Crown allowed any one man to select in those days, and my father was the second son of the original James Thomas, who came out from England in 1792 and selected land at Narellan in the Camden district. He married an Irish girl who emigrated to Australia from County Clare, Ireland. He named his farm "The Oaks" and it is a well-known name in that district today.

It was on this selection that they reared a family of 6 sons and 2 daughters, who were destined to play such an important part in the development of Kiandra and Lobs Hole. At the time he lived there, transport was the greatest problem confronting this young family, and bullock teams was the only method at their disposal to get food and material into the back blocks of the country. Therefore, he built up three bullock teams and three drays over the period, and when the Kiandra gold fields broke out, my grandfather and three of his sons took their three bullock teams to Twofold Bay. He bought three loads of everything including food that would be required on the gold fields.

To get there they had to climb over almost impossible country, including the old road of the Tangerwandler Mountain, which was almost perpendicular in places by putting the three teams on to the one dray. They were able to get them to the top of this mountain, one at a time, then over the Brown mountains, which were almost as bad and they eventually arrived at Kiandra. This was carried on until late into the second year.

They arrived in Kiandra in May and got their leading delivered, when it started to snow. Next morning there was about a foot of snow on the ground, the bullocks had disappeared, they had several large bells on, but none could be heard, so they looked around until they came upon their tracks in the snow, and these bullocks made a B-line to the tops of the range overlooking Lobs Hole. They followed their tracks down the mountain and eventually caught up with the bullocks down under the snow lines, feeding peacefully on good pastures. Incredible as this seems to be, no one could ever understand how a dumb animal could take the straight and shortest way to get out of the snow. They left them there and went back to Kiandra, as it was of no use taking them back into the snow.

They then packed their surplus provisions in the local store and carried camping gear and provisions down into Lobs Hole proper. When they arrived on Yarrongabilly River which runs through Lobs Hole, they found rich fertile flats and open ridges, all with good grass on them, so they went back and brought the bullocks down into Lobs Holes. Their father came with them on this occasion, and with his past experience of developing his own property, he showed them how to build a log hut, strip the bark and cover the roof. They stayed there until the snow thawed, then went back to Kiandra and took their drays out.

The following year, they brought three more loads from Twofold Bay. When they landed in Kiandra, they camped about a mile from the town. That night grandfather and one of the boys went into the town of Kiandra, or intended to go, and on the way down in the dark, my grandfather walked into a diggers hole about 6ft deep and in the fall he burst a blood vessel and died on the spot. That left the whole responsibility on the three brothers, James, John and Samuel. James did not like the carrying business, so my father John bought his team.

The Kiandra goldfields were booming in those days, and my mother's father, John Belcher, who emigrated from America, was an engineer and well versed in saw-milling. Father, having two teams of bullocks and my grandfather having the "know-how" of building and running saw mills. They entered into partnership and erected a sawmill, which they ran in partnership for several years. At that saw mill practically all the timber for Adaminaby and Kiandra was cut.

This mill was up in the snow belt and could only be worked for about six months in the year, so father selected 2,560 acres in Lobs Hole, to have winter country for the bullocks used for log hauling and delivering timber. The family would reside at the mill for about six months of the year and go to Lobs Hole during the winter months. During these winter months he would take the leading hands from the sawmill to Lobs Hole to help him erect buildings, fence the selection and clear the land. He named the property "Sheep Hill Station".

There was some very fertile land where the homestead was, and he soon had a first class orchard established with every kind of fruit growing to perfection. They clear country and established a good vegetable garden. With milking cows, greens and poultry we were living on the fat of the land.

Schooling was then the main problem, as Kiandra was the closest school, which was over nine miles, we were then sent to board at Kiandra where my early school days were spent. After three years, Lobs Hole began to develop and there were enough children to start a Provisional School. I spent the remainder of my school days there spending all my holidays on the roads with my father and his teams.

I note in your letter you are asking for information as to the history of Lobs Hole. It would be practically impossible to give you a true picture of the history of Lobs Hole without including part of the history of Kiandra, which is entirely another question, and to give you a history of both would cover a book, so I am confining my remarks as near as possible to my own personal experience and observations.

As the Alluvial mines in Kiandra were slowly cutting out, and the harsh winters there, many were leaving the district. This affected the saw milling industry, together with the fact that another saw mill was established at the foot of Conner's Hill. This made the competition in the milling industry very keen, so when that industry was closing, the copper mines at Lobs Hole started to work, this put a new industry on the door-step of our selection.

Three enterprising young men opened up the Lobs Hole copper mine, named Harry Beekman, Julius Forstrum and William Forrester. They sank a shaft on the load of copper that was evident to the surface, the deeper the shaft; the wider the copper lead became. When they got down about 60ft the seepage of water troubled them, as they had no pumping gear, and had to bail with a hand windless and bucket. They also had to haul all their copper etc to the top by one windless. So they started to drive along the side of the load and were getting a fair quantity of copper out, and soon had a good quantity of copper piled at the surface. Then the question arose as to how to get it to market.

My father took the contact to remove it all to Gundagai Railway. It was a colossal task to get it out of Lobs Hole. As it had to be taken up over that is known as the Toll Bar Road, which was almost perpendicular in some places. We had two drays and put 50 cwt on each fray when 18 bullocks could pull one dray over all the hills with the exception of the Toll Bar, we had to double back there and put 26 bullocks to pull it up the Toll Bar, and by this method we were able to take out approx 50cwt per day on each dray, equal to 5 tons on each trip. But when we got to the top of the mountain we could only take half a load from there to the Main Road, through Yarrongabilly, dump that on the road and get the other half. This method went on for several years.

In the meantime a man named Charles Blackman had selected a full block alongside my fathers sheep station property. He had a family of 5 children of school age. This rose the status of our school. He fenced and improved his property. In the meantime the copper mines put on a double shift to work the mine. Many workers were married men with families, so that helped the school again. With the extra men working underground, the old hand windless became a real problem. The syndicate then decided to put in a steam plant which was capable of doing all the hauling and pumping. This was bought and eventually arrived at Gundagai. By this time I was of age to drive one of the teams.

My father and I got the contract to deliver this plant to the mine. The boiler was 6ft in diameter and 10 ft long. A very top-heavy load to haul over such rough country. So the miners agreed to help us bring it into Lobs Hole. We had to come round some steep grades and could only prevent it from capsizing by having two long levers chained on to the top side of the wagon and six men swinging on those levers. We eventually got to the top of the Toll Bar, where there was 15chn of almost perpendicular mountain where we had to take that down. The miners supplied a very long steel rope 3/4" thick, this was tied to the back axle of the wagon, put twice around the butt of a huge tree and with the four wheels of the brakes screwed up we hauled it gently over the summit. Next we tied a huge tree on to the back axle and put a sapling through the two back wheels to lock them, we proceeded down the mountain, landed the Boiler at the bottom of this steep incline without a hitch. We then had the heaviest load ever attempted on the other wagon, all the pumping gear, winches, etc, which was 1 ton heavier than ever attempted previously, but having a bigger steel rope than we ever had before, we decided to give it a go.

All went well until we got within about 8chn of the bottom when the wheel ruts had been washed out and had no loose gravel to grip on, the wagon started to gain momentum, the men on the wire rope kept increasing the pressure on the wire rope to steady the wagon, until the rope cut into the wood of the tree and jammed, then broke. The wagon gained speed and ran on to the bullocks piling them in heaps and two were under the front carriage of the wagon when it stopped. We had to cut yolks to free the bullocks, six bullocks in front of the team the wagon passed, and we used those six bullocks to pull them out of the tangled mess. We finally sorted them all out, the two under the wagon were dead, another with legs broke and had to be destroyed and several injured.

There was one redeeming feature, we were over the worst of the road, so we called that a day. It was the only accident we ever had during the many years carting into Lobs Hole. So the next day, we mustered reinforcements of bullocks, of which we had plenty, then brought them to the scene of the accident. The following day we landed the steam plant at the mine safe and sound.

Next a man named Frank Brown came along a wanted to buy father's Sheep Station Hill property for the purpose of breeding horses suitable for transport in Sydney, as there were no motor lorries in those days and all deliveries had to be made by horse and lorry. My father eventually sold his property, and also sold him a snow lease held at the "Eight Mile Dam". This dam was built to work an open cut gold mine known as the 'Eight Mile Claim".

This dam is still there and is situated approx 3 miles on the Kiandra side of the Cabramurra Road. Frank Brown build a summer residence for his Manager, John McGregor, close to the Eight Mile Dam, also yards and stables to handle the horses and graze them for the summer months. John McGregor then selected another full block in Lobs Hole, adjoining this property, then my father having sold his Sheep Station Property became eligible to take up 2,000 acres closer to the Yarrongabilly River, there he build a good residence on "Sheep Station Creek" which he named that property after.

There was a stock route running through Lobs Hole, which was never used. It had fertile flats from the copper mine to where it junctioned into the Tumut River. Father had his eyes on that stock route with the idea of getting it canceled and added to his Sheep Station Creek property. He got up a petition to have the stock route altered to go through the station over O'Hares Hill and to the Tumut River where Sue City is now situated. He also applied to the Government to build a bridge across the river at that point. All the lease holders signed the petition to have the alterations made and a bridge built over the Tumut River to give the sheep owners of the leases an outlet from the Snowy Mountains through Tumbarumba. This was immediately granted and the Government called tenders for the bridge.

The successful tenderer immediately approached father to bring his bridge building plant from Gundagai on to the new site where the bridge was to be built. This had to come through Tumbarrumba and when he landed on the top of the site overlooking the bridge there was no possible way to go straight down so it had to be taken down a ridge about a mile upstream from the bridge site. All went well until he got about 15chn off the bottom, which was almost perpendicular. He arranged with the contractor to supply long 2" hemp ropes which were tied to the back axle and 3 men on each end of those ropes which were twice around a tree, the wheels locked and a huge tree on behind. We slowly but surely landed the bridge plants on the flat below. The men helping threw their hats in the air and gave three cheers, but one quiet observer said "but how are you ever going to get the wagon out."

It was also arranged in the contract that the bridge builders was to cut a road around gradually creeping up to the point of this hill and then zig zagging to the top of the ridge. So we had no trouble getting the wagon out. The bridge contractors had the plant on the job, but had not made any definite arrangements about the hauling of the bridge timber, which had to be brought from Paddy's River, about 16 miles away. So my father then agreed to haul the timber.

That meant we had two contracts on our hands, shifting the copper and hauling the bridge timber. In order to overcome this difficulty we employed a man and 10 packhorses to carry the copper from the mine to the top of the Toll Bar. This turned out to be a huge success and the packhorses could take it out as fast as the miners could haul it up with the steam plant. The one team left on the copper carting had a much quicker turn around and was able to keep the copper away reasonably well until the other team had finished carting the material to build the bridge.

When the bridge was built it proved to be a boon to the sheep owners and the stock route down the river from Lobs Hole was no longer required. Father made application to have it revoked and added to his 8,000 acre property, which built him up to a full area. From then on, we had two flats we cleared one, sowed with oats, the other for maise, pumpkins and potatoes. We were able to supply all the miner's requirements.

The steam plant was now working smoothly and the miners getting the copper to the surface quicker, but with the team of 10 pack horses we were able to cope with all the demands made upon us of shifting the copper to Gundagai. By this time my elder brother, George was driving one team and I was driving the other, thus leaving father more time to take care of the home and cattle. He then started a butchering business, which made a market for our cattle on the hook. So we had a complete team working amongst ourselves.

All went well until the 20th August 1901. I will never forget that if I live to be 100. We were coming back to Lobs Hole with the two teams to lift the winter stock pile of copper, we camped close to Blowering Station. My brother decided to cross the river to visit some friends. The river was running very strong at the time, so he asked the two Lambert boys to show him the best crossing, they decided to go with him to see him across the river safely. One of the Lambert boys rode across the river and George followed him, after crossing the main, As Lambert turned his horse to go back, the horse my brother was riding was only partly broken in, and wanted to turn back and follow, when he was held with the reins he reared on his hind legs and fell over backwards on top of my brother. He evidently had his skull fractured in the fall. The river washed him down into a big whirlpool in the bend and he never rose again. After six days search the body was found about 2 miles down stream.

From then on, we had to employ a driver for one team, and business went on as usual, but the whole management and responsibility fell on my shoulders. I was then 17 years of age and when it came to keeping books and business principles, the ordinary public school education was now sufficient. So I took up a correspondence class and studied commercial law. In those studies the first portion, double entry book keeping and business principles which helped me considerably in my occupation. I eventually completed the course, which has helped me through life.

All went smoothly in our business until 1903 when the bottom fell out of the copper mines. So the miners decided not to raise any more copper to the surface. They sank the shaft deeper, the drow tunnels along the edge of the copper load, to open it up and if the price rose to its normal level, they could get the copper out much quicker and if not they would have a better chance of selling it to a company, which they eventually did.

The manager of that company expressed the view, that by putting in a larger water plant to do the hoisting and pumping to build a smelter to take the slag from the copper and by cutting a road on to the main Gundagai highway at what is known as Middle Creek, they would shorten the rougher part of the road and the carriers could take half a wagon load per time, this would cut the transport export expense.

This idea no doubt would have been successful I the price of copper had risen. But it did not rise. So the company estimated it would take ten years to put the mine into full production, so that put an end to the copper carting for at least two years. The company did not want the steam plant, as they intended putting the bigger water plant in its place, this plant was too valuable to leave there to rust, so we eventually agreed with the original miner to take it back to Gundagai with their assistance.

We took the first two load of approx 4 tons up the Toll Bar in two drays, then it came to the big haul to take this boiler up. It had to be taken out on a dray also. It was a very top heavy load. We put 28 bullocks on to this load and eventually got it out safely to the main road and it fell to my lot to drive the team with the awkward load. I eventually got to Gundagai. I then left the copper mines for 2 years and took the teams into the wheat and chaff district. There was a big demand for carriers and I did exceptionally well.

Then a big drought overtook the district, the crops failed. When the wool season was finished I came back to Lobs Hole and on my way back I picked up two very high loads of large pipes, when were to convey the water from the channel head down to the mine level for the purpose of driving the turbines and pumps. By this time the smelter was almost complete, the road cut into Lobs Hole, and it looked like a hive of industry.

They eventually had everything working to schedule and for about two years Lobs Hole made great headway. When the mines were working and the smelter, the carting of copper started to move again and for 2 years they put a lot of copper through the smelting works.

One of the original miners had every confidence in the success of the copper mines, applied for a license and built a huge hotel, a police station was built, so it seemed like a prosperous place. I then selected another 2,500 acres on the southern side of Lobs Hole, therefore my father was the first man to select in Lobs Hole and I was the last.

I fenced the land and improved but it meant I would have to stay there 5 years before I got full title to the land. In 1909 I was married in Coolamon and took my wife there as a bride. We were very happy there and things were prospering until 1918 when all the copper opened up by the previous miners had been taken out and the company had spent most of their available capital on the surface and had not sufficient money to further develop the mine.

Rabbits came there in countless millions, which practically destroyed our winter feed, which meant we had to take our bullocks to the Riverina during winter for grass. We then decided to sell out. Buyers were very hard to get in that country, so we eventually exchanged the Lobs Hole property for a property in West Wyalong.

In April 1913 I loaded my furniture on to the bullock wagon and left Lobs Hole I then entered into an occupation of farming and grazing and professional land valuer, which I have successfully carried on since. Today, my wife and myself have 79 years of pioneering work behind us and I am pleased to say we are both well and happy and hope to spend may more years of our life together.

Yours faithfully CJM Thomas (FCIV)

REPORT WRITTEN BY MARGARET HUDSON FOR THE COOMA-MONARO EXPRESS PAGE 7, 30 AUGUST 1956

The House on Sheep Station Hill (1884-1956)

Seventy years ago, the sheltered valleys of the Yarrongabilly River supported one of the many lusty pioneering communities that toiled and sweated their way through Australia's early history. The soft deep folds and sheer rock walls of the surrounding hills echoed with the crack of whips and the ring of axes; the rivers were splashed with and muddied with the crossing and recrossing of bullock teams; and the gravel and rocks of the valley floor were crushed and washed for gold. And in the mornings, the warmth of the sun spreading from the mountain ridges down to the pastures below brought to these courageous people a deep love of the valley that was their home.

The valley sheltered them; the valley provided water and food for their stock and timber for their homes. The rest they could do for themselves. From Kiandra and Yarrongabilly they had made their way down to Lobs Hole with bullock wagons and packhorses heavily laden with food and tools and blankets. The women and elder children rode on the horses or on top of the load and the younger children were carried in boxes strung on either side of the packsaddles.

Camping under the wagon at night, they travelled slowly over the well defined bullock tracks of the plateau to the final descent past the Three-Mile Dam or down the steep slopes of the Toll Bar Ridge where bullock teams had to be lowered with wire ropes.

One of these early settlers was John Thomas of Camden who came to Lobs Hole in late in the 1840's. Approaching the valley from Kiandra, he kept to the left bank of the Yarrongabilly River and built his home beneath Sheep Station Hill. It was a large wooden……….Thomas made a bullock track up to the house and in the side of the hill he cut out a small storage space for butter and eggs. He and his wife then settled down to life in this pleasant fertile valley where people worked long and hard yet frequently lived to be over 90.

Thomas went in for cattle and during the long days of summer, he rode around his stock as they grazed on the unfenced pasture of the snow country. Every autumn the cattle were mustered and driven down to the shelter of Lobs Hole. When winter stocks of food had been brought in and snow lay deep on the surrounding hills, Thomas and his neighbours had time to visit one another and to spend long evenings in front of the fire discussing the affairs of the valley and swapping the latest news from the Kiandra gold fields.

John Thomas's first two children were sons. Then in 1884, 50 miles from a doctor and attended by an untrained woman, his wife gave birth to their eldest daughter, Olive. Olive was born with talipes of both feet. Her toes were pointing upwards and her feet lay along her shin bones. Her father long accustomed to relying on his own ingenuity, improvised splints from the stiff covers of a book and bound up his daughter's feet. They grew to be quite normal and it was only much later when Olive was training to be a nurse that she had any further trouble.

A second daughter, Tasmania, was born two years later and was still very young when their mother died, leaving the two children to the care of a series of housekeepers. One of Olive's earliest memories was the wedding of one of these housekeepers to John Gilbert, her father's stockman. The bridegroom was said to be 90 years old - the first white child to be born in Melbourne. The parson who performed the ceremony came from Tumut and the bride and groom rode to Yarrongabilly Village to meet him. It was a grand wedding. The verandahs of the Thomas's house were enclosed with tarpaulins and there were horses tied to every fence and tree. Never before had the children seen such a gathering or such a spread of food.

Being several years younger than their brothers, Olive and Tas relied on each other for companionship and the happiness of those early years was only marred by the normal childhood illness which in that secluded valley, constituted a crisis difficult to appreciate today. Olive, when she was still a very small child, caught German measles. As was usual in those days, the windows in her room were kept tightly closed. She was not allowed anything to drink and a large fire was kept burning day and night. She became desperately ill and for some time her life seemed in danger. Greatly alarmed, her father……Tas finally went down to the creek and filled two bottles. Olive drank it all and the bottles were refilled again and again. Later that evening their father returned afraid to ask if his daughter was still alive.

He had ridden a hundred miles in one day and at the last river crossing his horse had put his foot in a hole and fallen, rolling over on Thomas and injuring his neck. But the strain of the day fell from him as he went to Olive's bedside and found she was better. By giving her sister plenty to drink, Tas had anticipated the doctor's instructions. The windows were flung open and the patient slowly recovered. By the time Olive was allowed to get up again, the leaves had fallen from the fruit trees and Lobs Hole had settled down for the longest and most severe winter the children could remember.

The family's winter food supplies brought into the valley each year before May 24 were calculated with a wide margin. But this particular year, the snow remained on the encircling hills longer than ever before and the food situation became serious. Finally Thomas's elder son George set off with a packhorse for Kiandra via the frozen Three-Mile Lake. It was a long slow journey with the horses sinking deeply into the snow at every step. In the evening when George still hadn't returned Thomas and the other children took lanterns and climbed up out of the valley on foot, calling as they went.

Finally they received a faint reply and George appeared out of the night with a laden packhorse and a badly frostbitten foot. The winter dragged on and although the snow finally melted from the mountains the summer was weak and uncertain. One Christmas morning the children work to see the cherry trees already laden with fruit bent low under a heavy fall of snow.

When Olive and Tas reached school age their father sent them to Kiandra to attend the little school on Township Hill and to board with their Aunt Mary who lived in a fine house surrounded by tall poplar trees. During the winter when snow lay deep in the ..... George would put on his snowshoes and carry his sisters on his back up the hill to the school. Later, when they were older, Olive and Tas had snowshoes of their own. These snowshoes were home made and were waxed with a substance known as Moke. The shoes were held on by a single strap over the foot and to each was attached a cord. The other end of the cord was fastened to the wearer's belt so that the shoe could be easily recovered if it fell off.

During the summers spent in Kiandra the children swam in the Mill Hole - a wide deep section of the Eucumbene on the Tumut side of the town; they watched the mustering of brumbies on Long Plain and wandered among the gold diggings playing in the water…..Kiandra in those days was still a prosperous town. The first boom of the gold rush had passed but the streets were lined the shops there were two hotels, a dance hall, courthouse and jail, and many fine houses.

The Chinese population of the town lived down by the river, and the children never ceased to be fascinated by the customs of these strange people. They were irresistibly drawn to the cemetery after each Chinese funeral to see the roast pigs and the sweets, which were left behind the grave and the piles of crackers, which were lit from the bottom and went off in a series of coloured explosions. On one occasion the sight of so many sweets lying abandoned on the grass was too much for the little girls. They waited until the mourners had gone and took some home. Their Aunt was naturally horrified. Although it was dark, she sent them straight back to return the sweets to the grave. The dark walk back to the lonely cemetery was punishment enough.

The children had not been in Kiandra more than a year when their father brought them home and put them in the care of a tutor. Just out from Ireland the tutor, Mr Menzies considered the crude health of his two charges to be unladylike. In an attempt to make them pass and genteel, he does them every morning at eleven a… with turpentine. Tas was the first to rebel. She told her father and the unlucky Mr Menzies was given a month's notice.

Fortunately it was about this time that the parents of Lobs Hole clubbed together to build a small provisional school. Olive and Tas attended for several years. They still remember in the winter picking a flower from their garden and leaving it overnight in a small pool of water. Next morning it would be frozen in a solid block of ice ready to be presented to the teacher. In the afternoons when school was out their playground was the valley with rivers to fish and swim, …which hated the eastern end of the valley.

There were gold diggings to visit and prospectors to talk to and it was an enterprising child who didn't possess a matchbox full of gold, which was compared and bartered like marbles. There was the excitement of watching the bullock teams being lowered of the rock face of the Toll Bar by .. surplus stockmen as they made the final descent of .. Crossing with wheels chocks and brakes full on. In the evenings when the men came home and set with their legs stretched out in front of the huge stone fireplace there were stories to listen to. They told the tale of the big blue-gray wallaroo which came silently up behind George when he was out shooting and pinned his arms to his side; there was the ..story of the dead butcher O'Hare who it was said could be seen on moonlit nights riding over the hills with his head under his arm.

Inevitably the… another favorite topic was the heavy winter when the cattle had been caught by an early fall of snow. According to one of the miners, "the snow was so deep in Kiandra that I had to sit on top of a telegraph pole to tighten my shoes". Then I moped about and suddenly looked down and there , so help me, was Mother Mary, the publican's wife frying steak.

There was no end to the tales from the goldfields and sooner or later, visitors would hear the story of the family with three teenage sons. One evening, so the story went, when the sons were out at a dance, an old married couple selling vegetables called at their home. The boys' parents offered the old couple the big double bed usually occupied by their sons. Two of the boys came home early from the dance and realising what had happened went to sleep in another room but when the third boy came home late, he crept in quietly and got into the double bed as usual. In the morning he woke up entangled in the old woman's hair and found that he had spent the night sleeping between husband and wife.

Everyone dropped in to see John Thomas and his family. His was the largest house in Lobs Hole and his hospitality never failed. The aspiring politicians dropped in and stayed to address whoever cared to listen; the police and black tracker from Tumbarrumba dropped in sometimes for a chat and on one occasion with a warning that the murderer of Constable Guilfoyle had been seen in the mountains. Clergymen of all denominations called to conduct services, which were attended by everyone in the valley. From time to time, Indian hawkers rode down the Toll Bar and at the sight of their silks and ribbons and bright jewelry, Olive and Tas quickly overcame their distinctive fear of the strange brown faces.

The two girls were alone a great deal particularly in the summer months. One memorable morning after the men had left with the dangers of playing with their usual warnings about fire or ?? Olive suggested a walk over Sheep Station Hill to visit their former housekeeper, Mrs Gilbert. There had been very little rain that year and the grass was long and dry. "I wonder" said Tas, "if it would burn?" She dropped a lighted match and almost immediately the grass at their feet burst into flames. Terrified they tried to stamp it out. But it was useless and they were forced to turn and run for their lives. Very soon the whole hillside was ablaze. The flames followed them up the hill and down to their home on the other side. Snatching up a few belonging, the girls rushed for shelter between the rocky walls of the creek.

The fire completely destroyed their home and took the men a week to put it out. John Thomas built another house further down Sheep station Hill on the banks of Sheep Station Creek. Then he packed his daughters off to school at Yarrongabilly Village. Olive and Tas boarded with Mrs Gibbs at Jounama Station and rode four and a half miles to school every day. Sometimes they walked and competed to see how many snakes they could kill on the way. When they reached High School age they went to board with friends in Tumut and for four years saw very little of Lobs Hole.

On the few occasions when they did come home, they travelled as far as Yarrongabilly Village by coach - Tas on one occasion making the coach two hours late by reading lurid extracts form "A Bad Boys Diary" to the coachman as he drove up the Talbingo Hill. When their schooling was finished the two girls came home to help in the house. By this time copper mining had started in the valley. There were three main shafts, a drive going right under the river and a flying fox going over it. The copper bearing rock was hauled to the surface in great iron buckets then crushed and melted into blocks. The blocks were then loaded on packhorses who toiled up the Toll Bar to the plateau above. Near the road, the blocks were unloaded and stock piled until there were enough to fill a bullock wagon for the comparatively easy run down to Tumut.

The miners camped in tents or built themselves rough huts. For meals, they had the choice of two boarding houses. The mine manager and his assistants lived in comfortable houses built overlooking the mine workings and the river. This influx of population added greatly to the social life of the valley. There were cricket matches on the flats beside the river, tennis courts were built and the boarding houses were renowned for their gay parties. Dances and parties meant very little to Olive. Even after she had left school she preferred riding and shooting to social activities. Tas on the other hand thought nothing of packing her best frock and shoes in a saddlebag and riding ? miles up to Kiandra for a dance in the local hall. She and a school friend, Sylvia would ride up the narrow track that leads around the rocky faces of the "walls". After the long ride, they would change in one of the hotels and then hurry to join the crowd of young people - shepherds, drovers, prospectors and tourists - who were already dancing ……..violins and mouth organs.

During their visit, Mrs McMiles and Mrs Bellingham mentioned that B…This track down the Walls certainly corresponds with the description of the hazardous route down the rocky cliffs used by Captain Starlight and his followers. Race days, too, were great occasions in Kiandra. Horses were imported from Adaminaby, Tumut and Cooma. The ladies wore bright sashes on their frocks, there were bookies and the gum trees … woman on horseback with one child on their lap and others clinging to their waist as they cantered up the main street and out to the racecourse. In the winter there were the snow show races. Rollicking affairs according to a local poet ….

Shortly after Olive and Tas returned home from school their father engaged a lovely and competent housekeeper whom he later married. The girls were very fond of their stepmother and it was a great blow to whole family when she died in the Tumut Hospital having two little boys - aged three and one. Tas, then only 17, took over the responsibility of bringing up her stepbrothers. Olive in the meantime had married. She had first met her future husband when she was 14. She was, even then, an experienced horsewoman, and on one occasion when the men were away mustering, she was deputed to see a visiting drover, William Speer, through the run.

Later, when Olive was 17 and William Speer became the manager of a Riverina Estate, they met again at a ball. A year later they were married with a wedding ring made from gold found at Lobs Hole. A few years after Olive had left for the western plains, Tas married Albert Bellingham - a young man who had come to the mountains for his health. After the fire which destroyed his first homestead John Thomas had sold part of his run to a Mr Brown. Brown started horsebreeding and built a large house on the eastern sloped of Sheep Station Hill. Mack McGregor was appointed manager and with him came Bert Bellingham then a very delicate youth. The climate of Lobs Hole however soon restored the young man's health and for many years he spent the summer in a small hut beside 8-Mile Dam (Dry Dam) looking after Brown's stud horses.

When Tas was 18 she became his wife. Like Olive, she was christened, confirmed and married in the Tumut Anglican Church. The young couple remained in the mountains for several years after their wedding and then left for Sydney. So it was 50 years ago that Olive and Tas left Lobs Hole. When they returned as guests of the Snowy Mountains Authority, the people and the life they had known had vanished almost without trace.

On the Cooma side of Kiandra, a long poplar tree was all that remained of the Aunt Mary's house. The school on the hill had disappeared, so had the dance hall, the stores, the hotels and practically all the houses. …..had silted up and become almost indistinguishable from the rest of the river. But the change was greatest in Lobs Hole itself. The mines had closed many years before when the price of copper dropped and the shafts were abandoned and overgrown. The mine manager's house, where Olive aged 18 had been given a garden party to celebrate her forthcoming marriage was still standing but had fallen into disrepair. The tents and huts of the miners had gone and stone chimneys and a few scattered timbers were all that remained of the boarding houses.

Occasional glimpses of poplars and fruit trees were the only indication of the homes and families that had made up that prosperous community. From the copper mines, Olive and Tas followed the river down to Wilsons Crossing. There, from the ruins of the Abode Hotel, they turned towards Sheep Station Hill and walked slowly up the overgrown path that followed the course of the Sheep Station Creek. A kangaroo on the hillside stopped to watch them as they passed. Half a mile up the track on the banks of the creek the walls of an old wooden house leant drunkenly inwards. The roof and flooring had gone and timbers were rotting on the thick damp grass. In the garden, a few flowers were struggling for existence among the weeds. Two old trees were bent low with unpicked fruit.

Standing side by side, the two sisters struggled to keep back the tears as they gazed down on the ruins of their old home. But despite the rotting timbers and the overgrown tracks, they knew in their hearts that the spirit of John Thomas and his neighbours could never be erased. The memory of them would remain to walk in the valley, not furtively by moonlight like the ghost of O'Hare, but boldly and openly in the sunlit pastures that they loved.